Reflections – Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites at the National Gallery

The exhibition explores the influence of Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait and the works of the Pre-Raphaelites and their successors. Acquired in 1842, just 18 years after the National Gallery was established, Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait was the first early Netherlandish painting in its holdings and made a lasting impact on those who saw it. Especially young artists such as Millais, Hunt, and Rossetti, who were enrolled at the Royal Academy housed in the same building on Trafalgar Square and would’ve easily seen it. The exhibition shows references to the painting in the Pre-Raphaelites work in the attention to symbolic details such as the shoes, oranges, lit candle and the high level of finish. The most notable feature of Van Eyck’s portrait is the convex mirror in which is reflected the backs of the two protagonists and between them two male figures, the one in the blue coat long thought to be Jan van Eyck himself.

A quirky example of an artist’s self-portrait reflected in a convex mirror can be found in a small oil painting in the Katrin Bellinger Collection by the Belgian artist Edouard Duyck (Fig. 1). Dated to 1883 this lively portrait reflects the artist as if he is looking into a convex mirror. The details of the room behind him are suitably distorted – thus we see the window to the left bend inwards as does the easel to the right. At its centre the viewer is faced by the artist who smiles back at us.

For many artists, the use of the mirror provided an opportunity to place themselves firmly within the subject of the painting. An early example of this can be seen in William Orpen’s painting The Mirror (Fig. 2, Cat. 40) in the National Gallery show. Here the painting is dominated by a circular mirror which reflects on a miniature scale the artist at work at his easel, a woman standing by his side. Orpen was fascinated by mirrors and repeatedly used them to capture his own self-image at a distance, his obsession with them linked to his own deep-felt insecurity which apparently stemmed from his overhearing as a child his parents bemoaning his appearance.[1]

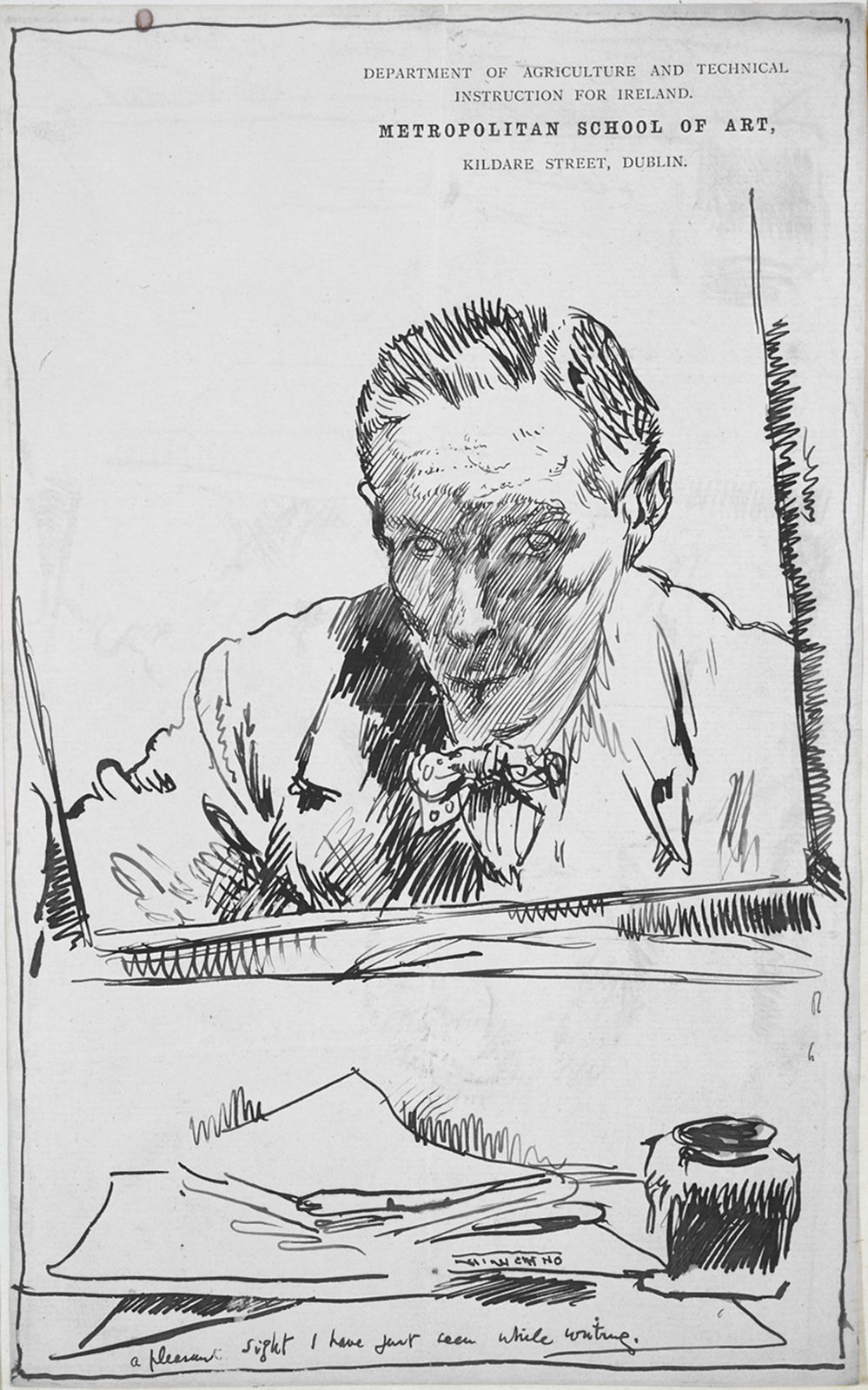

Between 1908 and 1912, Sir William Orpen made a series of self-portraits in spite of an intense self-consciousness which often surfaced in his works. In his Self Portrait looking in a Mirror in the collection (Fig. 3) he makes a comical reference to his looks, inscribing along the bottom ‘a pleasant sight I have just seen while writing’. This drawing within a letter to his wife Grace is executed on the headed paper of the Metropolitan School of Art Dublin where Orpen taught.

One of Orpen’s pupils at the Metropolitan School of Art was Leo Whelan whom Orpen considered ‘a promising youth’. He was influenced by Orpen’s use of the mirror device as can be seen in his painting The Mirror (Fig. 4) from the collection, first shown at the RHA in Dublin in 1912 when Whelan was just 20. Here Whelan depicts himself standing confidently with his leg firmly planted on the easel, palette and brush in hand studying his reflection in a large mirror. The mirror is framed by a velvety fabric which is held in place in the left foreground by a maquette depicting an Irish peasant group digging for potatoes, possibly referencing the Famine. A rare subject for sculptural treatment for this period, its inclusion suggests Whelan’s interest in Irish rural social subjects.

Ultimately, the use of mirrors became familiar motifs in British portraiture in the early twentieth century and allowed the artist to not only insert themselves in the pictorial narrative but also to explore their own identity and notions of self.

Reflections: Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites co-curated by Susan Foister, Deputy Director and Curator of Early Netherlandish, German, and British Paintings at the National Gallery and Alison Smith, Lead Curator of British Art to 1900 at Tate Britain is open until 2 April.

End Notes

[1] Stories, page 22. why it was that he was so ugly and the rest of the children so good looking. I began to think I was a black blot on the earth.

Fig. 1 Edouard Duyck, Self Portrait, as reflected from a convex mirror, 1883, oil on panel, 120mm. diameter, Katrin Bellinger Collection 2000-015

Fig. 2 William Orpen (1878 - 1931), The Mirror, 1900, oil on canvas, 508 x 406 mm, Tate

Fig. 3 William Orpen (1878 - 1931), Self-Portrait, Looking in the Mirror, circa 1909, pen and black ink on Metropolitan School of Art writing paper, 332 x 207 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection 2003-005

Fig. 4 Leo Whelan (1892 - 1956), The Mirror, 1912, Oil on canvas, 840 x 660 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection 2012-024